USA Health Magazine: After 30 days on life support, patient beats COVID-19

On May 15, as Matroy waited to be discharged, he talked with those who helped him battle the novel coronavirus and welcomed his wife to his room. Her arms open wide, she leaned over his bed and hugged him tight, whispering in his ear through a medical mask.

By Casandra Andrews

[email protected]

On Sunday, March 29, at 6:10 a.m., Matroy Browder called his wife, Sylvia, to tell her his health was not improving. He needed to be placed on a ventilator because of complications from COVID-19.

“It’s one of the hardest things I’ve ever had to do,” he said. “I basically had to say goodbye.”

A day earlier, Sylvia Browder drove her husband – a retired U.S. Border Patrol agent and U.S. Marine – to the emergency department at University Hospital. Diagnosed with COVID-19 at an urgent care clinic a few days before, Matroy’s condition had rapidly deteriorated.

“We were trying to fight it at home,” Sylvia said. When he began having difficulty breathing, they quickly sought medical attention.

All told, her husband spent 47 days in the hospital, with 30 of those days on a ventilator, a machine that breathed for him because he couldn’t breathe for himself. It was the longest the couple, married for almost 30 years, had ever been apart.

Because of restrictions placed on Alabama hospitals during the COVID-19 pandemic, no visitors or caregivers were allowed in the critical care unit where Matroy spent more than a month. The Browder family had to rely on physicians, nurses, respiratory therapists and other staff to help them stay in touch.

Sylvia said hospital staff would hold an iPad close to his bed so that she and their children could talk to him, offering encouragement and prayers. They also prayed for everyone involved in his care.

“The medical team was outstanding,” Sylvia said. “They allowed us to FaceTime. We called four times a day to check in because we had to know how he was doing. They did not hesitate to help.”

While Matroy was on life support, hospital staff took other steps to speed his recovery. They received photos of his family by email that were printed out and placed on the walls of his room. A colorful sign above his bed announced: “Who’s a fighter? This guy.”

His fight for life spanned more than a month. About two weeks into his hospitalization, Sylvia received a call to discuss end-of-life plans for her husband. At that point, his prognosis appeared grim.

“I told them, ‘not on my watch,’” she said, shaking her head. “I knew my husband had a story, and he would recover. That night, we all prayed for him and the whole team.”

Later, she learned that evening was when her husband began to improve: “There were some highs and lows, but we never gave up,” she said.

Maegan Tapia, B.S.N., R.N., an interventional radiology supervisor at University Hospital, served as Matroy’s primary nurse. A member of the serious infection disease team, Tapia volunteered to leave her regular post and exclusively care for those battling COVID-19.

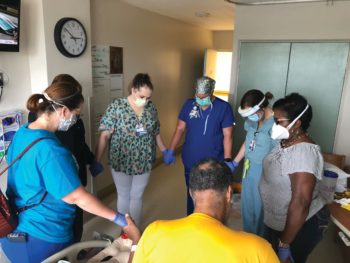

“Seeing him slowly begin to make progress was the encouragement we all needed,” Tapia said. “I remember the day he was extubated (taken off a ventilator). We stood outside his door holding hands and praying. It was me and other nurses in the unit along with the primary attending. Tears streamed down our cheeks as we saw just how well he was doing. It was a day I will never forget.”

On May 15, as Matroy waited to be discharged, he talked with those who helped him battle the novel coronavirus and welcomed his wife to his room. Her arms open wide, she leaned over his bed and hugged him tight, whispering in his ear through a medical mask.

“It really brought our family and friends together,” Matroy said of his illness. “People were praying for us from Georgia to California.”

Kristopher Haskins, BSN, RN, a nurse manager who oversees the Arnold Luterman Regional Burn Center, the wound center and critical care unit for COVID-19 patients at University Hospital, led the effort to ensure Matroy had a jubilant send-off.

As word spread of his departure, clinical staff began visiting Matroy’s fifth-floor hospital room. Some even came in on a day off to wish him well.

“You are a gift to every single one of us,” said a nurse clad in a mask and blue scrubs, raising her arms and cheering after she entered his hospital room.

Sitting on the edge of his bed, Matroy told them how grateful he was for the excellent care he received. The group formed a semicircle around him, bowing their heads and clasping hands. He began to pray, his voice strong and clear: “I want to thank you, father God, for bringing us together. I ask that you create a permanent bond between us, since what you did for me was so spectacular.”

After 47 days hospitalized, he needed to regain the strength to walk again without assistance. As paramedics arrived to take Matroy to a rehab center by ambulance, dozens of hospital staff gathered, standing at least six feet apart, to line the fifth-floor hall for his departure.

“His recovery has given many of us in the unit hope, strength, and courage,” Tapia said. “It has given us the courage and strength to continue to fight this battle, to be the voice for the patients, to continue to advocate when others begin to lose hope.”

For much of the COVID-19 global pandemic, Mobile County led the state in the number of cases and deaths reported. When Matroy was released from University Hospital, Mobile County had recorded 1,559 cases of COVID-19 with 97 deaths from the illness, according to the Alabama Department of Public Health.

As Matroy was rolled into the hallway on May 15, joyful cheering erupted. A nurse handed him a pom-pom that he waved as he was pushed toward the elevators. When he exited the emergency department downstairs, he was surprised by a large crowd of family members gathered in the parking lot, including his children and grandchildren, who clapped and cried when they saw him.

Less than two weeks after leaving University Hospital, Matroy departed rehabilitation and finally headed for home in west Mobile. A few days later, on the last Saturday in May, he was surprised with a parade in front of his home that included border patrol agents, members of area Harley-Davidson groups, friends from church, his family and staff from University Hospital.

Two local television stations aired stories of his homecoming, showing a beaming Matroy, his wife, children and granddaughters waving to those who drove by.

“This is a testament and I want people to have hope,” Sylvia said of her husband’s illness and recovery. “We want to share hope with other people.”

A lifeline between patients and families

Maegan Tapia, BSN, RN, an interventional radiology supervisor at University Hospital, volunteered to care exclusively for those battling COVID-19 beginning in March 2020.

A member of the serious infection disease team at USA Health, Tapia was the primary nurse for Matroy Browder, a patient hospitalized for 47 days as he battled COVID-19. He spent a month on life support before gradually getting better.

Because of statewide restrictions banning most visitors and caregivers in Alabama healthcare facilities during the COVID-19 global pandemic, hospital staff members such as Tapia have become a lifeline between patients and their families.

“We are all they have each and every day,” Tapia said. “I’ve never before had to rely on an iPad to be the main means of communication between a family and patients. We’ve been fortunate to have the electronic devices for our patients and their families to communicate with each other.”

Often, a family member helps support a patient and his or her caregivers.

“Someone being at the bedside is pertinent,” she said. “They give us insight into who our patients are, and they offer encouragement for us to keep doing what we love, which is caring for others.”

The Browders, she said, are an amazing family who never lost faith during Matroy’s hospitalization. “I would regularly tell Troy that they may not be there physically holding his hand, but they were always holding his heart from afar.”

The Browder family called the critical care unit four times a day to check on Matroy.

At one point, Tapia was talking with Sylvia Browder by phone to go over her husband’s care directives, which guide the medical staff on his wishes for end-of-life care and other matters. He was making progress, responding well, and doing so much better overall, she said.

That’s when Tapia told Sylvia her husband was still technically considered a “no chest compression” patient if his heart stopped and resuscitation was needed.

“I’ll never forget her response,” the nurse recalled.

“She said, ‘Maegan, we made that decision when he was really sick because we did not want to risk the virus exposure to the staff caring for him.’ I couldn’t help but be touched by the idea of them making such a selfless sacrifice for the well-being of people they had never met before.”